by Howard Goldbaum

Cu Roi mac Dari was a legendary sorcerer, an evil magician who resided in the south of Ireland in the dim mists of the prehistoric Iron Age. He has given his name both to the mountain we climbed today, and to the stone fort near its peak. All that remains of Caher Conri ("The Fort of Cu Roi") is a tumbling stone wall, 350 feet long, and 14 feet thick, which cuts off a narrow triangle of land 2050 feet above sea level. Archaeologists classify this type of monument as an "inland promontory fort." With the fort guarding its entrance, and forbidding sheer cliffs protecting its other two sides, this small refuge on a remote mountain must have been a sanctuary to use when all else failed.

I first read of the legend of Caher Conri 20 years ago, as I began my research into the connections between Ireland's ancient monuments and her mythology. In the summer of 1979 I made my first attempts to photograph the fort at the summit. My dad designed a backpack which allowed me to heft a 40-pound aluminum case containing a large-format Sinar view camera up the mountain. But even after three attempts that summer, I was unable to get a clear shot from the summit where the fort is located. The weather would not cooperate.

The climb of Caher Conri presents certain difficulties, even for my younger self in 1979, and for today's group of Bradley students. For one thing, the first mile or so traverses wet bogland, with spongy vegetation covering sinkholes into which you can plunge up to your knees in peaty mud. Beyond that is a half mile of climbing through areas of loose rock. And always there is the threat of the clouds, which can descend suddenly, leaving you without vision, with a whiteness so profound that you lose all sense of direction. The person whom you saw just yards away one minute could become lost in the mist in an instant.

The next year, in July of 1980, I finally met with success. Using a more reasonable field camera, a medium format Bronica, I was able to climb to the top of the mountain and take a series of photographs showing the fort from above, with the entire sweep of the Dingle Peninsula stretching out below it, all in gloriously rare cloudless sunshine.

Now, 20 years after beginning this project, I'm still working on it. After photographing, researching, and recording oral traditions from some 160 different Irish archeological sites during eight previous visits to the country, I've determined that I need to return to many of them in order to collect new computer-enabled media: QuickTime Virtual Reality environments and digital video.

There have been many unexpected pleasures in continuing a project begun two decades ago. Perhaps the greatest pleasure has been in returning to visit some of the sources for the traditional material I collected on audiotape in 1979. Some of the men, in their 60's then, I found still alive and well when I visited them last summer. In June of last year I knocked on the door of Tom Farrell, who owns the farm where the Rathcroghan ceremonial mounds are located.

Since I hadn't seen or communicated with him in 20 years, I began with "You probably don't remember me, but..." He cut me off with, "Of course I do. You're Goldburn, right?" Close enough. Time has only dulled his memory a bit. Time has not changed Caher Conri at all. And myself???

The problems, of course, in returning to photograph the fort of Cu Roi in 1999 are twofold: will the weather cooperate and will I be able to keep up with my students and get my now 20-year-older knees to climb me and my equipment to the top?

Why is it so important that I complete the virtual reality images of this particular fort? Although it is an extremely photogenic pile of stones when the weather allows, it is the legendary story of Caher Conri which draws me back.

"The Tragic Death of Cu Roi mac Dairi" is one of a group of sagas which feature this half-demonic person with magic powers. There are numerous versions of it in early Irish and it is echoed in stories in Wales and even in Belgium.

At first Cu Roi was allied with the great hero Cu Chulainn, the Hound of Ulster. But after a ferocious battle in Scotland, when they were dividing the plunder, they did not give the magician Cu Roi his fair share. Although Cu Roi was, by right, able to claim as his reward the lovely lady Blathnad, Cu Chulainn wanted the woman for himself. When Cu Chulainn would not agree to turn his lover over to Cu Roi, the magician turned upon him, thrust him into the earth to his armpits, cropped his hair with his sword, rubbed cow-dung into his head, and then went home to his fort on top of the mountain. He took Blathnad with him and married her.

His fortress was impregnable. Not only was it situated on this forbidding, isolated mountaintop, but it was also guarded by Cu Roi's magical powers. At night, when he slept, he was able to make the fort spin around and around, confounding his enemies.

But Blathnad's love for Cu Chulainn was greater than the evil Cu Roi's magic. After Cu Chulainn's hair grew back and he regained his courage, they plotted the demise of Cu Roi.

Blathnad flattered her husband by telling him that the construction of the fort was not suitable for one as great as he. So the magician sent his warriors out to gather more stones so that the fort could be enlarged. While the fort was undefended, Blathnad hid Cu Roi's weapons. As he slept, she poured milk into the stream that runs down the mountain. Cu Chulainn and his men, camping in the valley below, saw the stream turn white, and knew that the time to attack had arrived.

They rushed up the mountain with a roar, and killed the evil magician. Blathnad and Cu Chulainn were reunited. (They didn't live happily ever after, but that's another story.)

This stream is today called "Fion Glasse" (White Brook). With just a little imagination, when the afternoon light glints off the rushing water, it again becomes a milky message.

We began our adventure around 9:30 this morning, leaving our B&B in Anascaul in fine weather, and ascending the "scenic route" mountain road that cuts northward up through the eastern third of the Dingle Peninsula. "Not suitable for heavy vehicles," the road sign said at the bottom of the hill.

We were well-prepared for a day of changeable weather: everyone had a daypack with warm clothes and a rain suit. Our hostess in the Old Anchor B&B had packed bag lunches for the group.

The road was marginal for a VW minibus. Barely the width of our vehicle, it even had grass growing up through its crumbling asphalt. Midway up we encountered a garbage truck headed the other way. One of us needed to back up until there was clearance. Either chivalry or the fact that he was bigger than me prompted my decision to give ground.

As we began our hike, the sunny skies of Anascaul became cooler and more hazy, with lowering clouds forming in the north west. I felt that safety was assured, as even in the extreme whiteout conditions of a storm (which I experienced in 1979), the since-installed posts placed every 100' enable climbers to descend safely.

Our climb took us through a beautiful and rare landscape of bog flora, with every flavor of green represented in the ferns, mosses, lichens, carnivorous plants, and miniature orchids that we saw. I stopped mid-way to shoot a 35mm virtual reality panorama for "insurance" should the planned shots from above not be feasible. I also shot some close-ups with the digital camera of the bog vegetation.

As we rose above the bog and into the final ascent to the ridgeline, the clouds fell to meet us and we were surrounded by a cold, wet, fog. Although it was obvious that our chances for photography were rapidly approaching zero, we voted to continue the quest for an audience with Cu Roi. Stopping at each marking post, we squinted through the soupy air until we could make out the next target. Eventually we reached the summit, explored the fort and waited an hour to see if the weather would clear.

After our unusual picnic, we finally abandoned hope of making any pictures at the summit and began our careful knee-wracking climb down the hill. Neither the students nor I were any worse for the effort, although we were exhausted and desperately in need of a laundromat to wash off the bog mud. But we all had a good story to tell.

The story, of course, is about Chu Chulainn, Cu Roi, and Blathnad. But it is also, for me, about the dignity of heritage, the wonders of history, the permanence of myth, the certainty of place, and the pleasures of teaching and passing on what is given.

Once again the fog forced me off the mountain before I could complete my work. I guess this means there will be another trip to Ireland.

Cahir Conri

Now reduced to a long, tumbled stone wall. The Iron Age fort of Con Ri guards an area that was once a tribal residence, with huts and tents for homes. (1980 photograph)

Seen from below in the descending fog, the fort of Cu Roi at the top of Cahir Conri is lost in the mist.

Photographed on the one occasion when my visit to its peak coincided with a clear sky, the stones of Cahir Conri are seen guarding their isolated promontory in 1980.

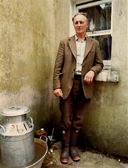

Tom Farrell, photographed in 1980.

At the midway point of the trail to the top of Cahir Conri, the group takes a rest. Click on the picture to see the entire QuickTime VR panorama (236 K).

Rebekah demonstrates that being properly dressed for mountain hiking does not necessarily mean that one has to abandon one's style.

Kellly rests momentarily by one of the posts situated each 100' to aid climbers when the visibility changes due to fog conditions.

Seen from a couple of yards away, the bog vegetation presents a thick tangle of variegated greenery, spongy to the feet and wet to the touch.

Close up, the individual bog plants are filled with intricate detail: miniature star-like ferns and tiny orchids.

Grateful for the lunches packed by The Old Anchor B&B in Anascaul, we gained the needed calories for the trip down the mountain and then posed for one last picture on the summit.

Emily, at the start of the climb, and afterwards.

Back